In deference to the bustle of the Holidays, and the still lurking specter of Covid-19, the Catskill Fly Tyers Guild held an online Zoom meeting for our December gathering yesterday. Our discussions this month revolved around a nice presentation by member Fred Klein, a tyer and historian of classic wet flies from the 1800’s and early 1900’s. Fred exhibits a true passion not only for tying these traditional patterns, but for fishing them regularly as well.

Mr. Klein, who makes his home in Pennsylvania’s Appalachian Mountain region, admitted to his fondness for hunting large brown trout with big, classic wet flies – something I can easily understand. He talked of the clear mountain waters in winter, and how he finds success with big natural looking flies like the Cochy Bonduu that push water and thus attract predatory browns in their more passive moods. Though my recent forays have been rewarded with a couple of flashy streamers that beckoned to trout in a more aggressive mood, I decided to tie a few of these subtle classics and give them a swing.

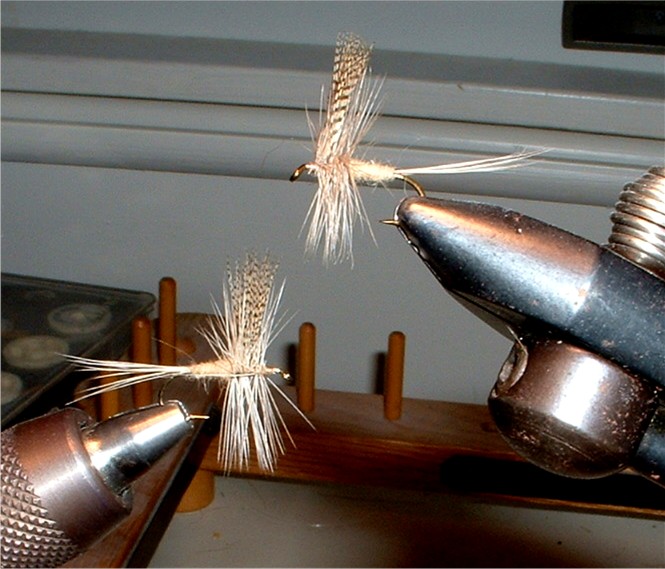

As we discussed the Cochy Bonduu, I thought of another long-time favorite of mine tied with peacock herl and furnace hackle, a fly I dubbed the Peac-A-Bugger. I have habitually used the dubbing loop technique when tying peacock herl fly bodies, whether for tiny Griffith’s Gnats or steelhead size buggers. Spinning the peacock herl in a loop produces a full herl chenille that I find more beautiful and much more durable than wrapped herl. Over the past 25 years, the Peac-A-Bugger has accounted for numerous trout up to five pounds or so, and several steelhead between eight and ten pounds, whether swung, dead drifted or stripped.

Our wild trout have many moods, and it makes sense to try offering both flashy, high motion patterns to attract aggressive fish and smaller, subtler natural patterns to appeal to those in more passive moods.

I enjoy the serenity of the classic wet fly swing, but winter isn’t the time to fish these flies shallow. Swinging them down along the bottom with a sinktip line has its own little bit of excitement built in. You may fish out your afternoon without a strike, but if you do feel a tug, experience promises that a take is likely to be a larger trout.

Winter has returned a week before Christmas, and there aren’t any more record high 64-degree afternoons in the ten-day forecast. The upper thirties will have to do as it stands right now. I can deal with that, at least if the winds are fairly calm.

During my years in the Cumberland Valley, I would often venture out in search of a Christmas fish. The beautiful wild rainbows that once proliferated in the Falling Spring seemed perfectly hued to celebrate the season. I wonder if there is a Delaware bow out there that I might convince to dance a Christmas waltz with me?